A Solway Sea-fever

The Solway Firth is the third largest estuary in the the UK. A place of indescribable sunsets and one of the highest tidal ranges in the world. Once infected by its landscape, there is no known cure.

Before Wiltshire, there was Cumbria. A mountainous land bordered by a sea whose waters cracked a wedge from the border and the Solway filled it with silt and sand.

I must go down to the seas again to the lonely sea and the sky

And all I ask is a tall ship and a star to steer her by

And the wheel’s kick and the wind’s song and the white sail’s shaking

And a grey mist on the sea’s face and a grey dawn breaking.

Sea-Fever by John Masefield1

To the west of my house, a river pours itself into the Irish Sea. From a calcareous birth under the limestone of Mallerstang Edge, the river cuts its ninety-mile dash to the sea, stopping, on occasion, to flood a city.

To the Romans, she was Itouva, a name borrowed from the earlier Britons who knew her sweeps and flexes and called her Ituna, ‘to bend’. Beyond the city, the contemporary Eden shapes lazy arcs through rich green pastures until Rockcliffe. Here, the estuarine elements of the Solway Firth begin to blend with the salt-free freshwater below orange sandstone bluffs. Below the churn of the fresh and the salt, three great sand banks that once bore armies crossed the estuary.

The Peatwath crossed the shallow Eden below Rockcliffe, the Sulwath spanned the mouth of the Border Esk, and the Sandwath, furthest west, traversed a broad bank from Drumburgh to Dornock. Ancient arteries of peat, mud and sand; sutures that tie the jagged edge of nations together.

Solway isn’t the way of the sun, though the sunsets here are indescribable. It is the way of sul, the Anglo-Saxon word for mud. Edward Longshanks fell foul of it in 1307. He died of dysentery while camped on the marshes waiting to cross the Sandwath. A single pillar marks the place, encircled by rusted iron railings and grazing salt-beef cattle. Longshanks still waits outside the Greyhound Pub in Burgh-by-Sands, a sword and helm in hand, inclined to hammer the Scots. It’s the finest statue in Cumbria. The King’s wasted body lay in State at St. Michael’s Church for ten days. His heir, Edward II, was later proclaimed King in Carlisle.

The sleepy sound of a tea-time tide

Slaps at the rocks the sun has dried

Too lazy, almost, to sink and lift

Round low peninsulas pink with thrift.

A Bay in Anglesey by John Betjeman2

It’s a fast road out of Carlisle, west, towards the sunset, which is at odds with the unhurriedness of life on the island. It is where happiness is in the anticipation, not the fulfilment. Locals still call it the island, a single brown contour ring reaching out of the Solway marsh, a land bridge between two estuaries. To the south, Morricambe Bay was once a natural harbour for the Roman galleys that brought olive oil and garum to Hadrian’s Wall.

The mosses, peats and waths of the Solway Firth have always been an end and a crossing. When the tide is out, the water’s edge can be a mile away. An imperceptible causeway connects the end of arable fields with the beginning of the marsh. It is like stepping off the chartered into the unchartered. Deep channels cut through the marsh that still hold water during the hottest months. The marsh grass is out of this world, pricked with sea pinks, close-cropped by sheep, and alive to the sound of ascending Skylarks.

Armeria Maritima ~ Sea Pinks ~ Thrift ~ Sea Thrift ~ Sea Pink ~ Cliff Rose ~ Cushion Pink ~ Lady’s Pin Cushion ~ Marsh Daisy ~ Sea Gillyflower ~ Sea Grass ~ Cliff Clover ~ Mary’s Pillow ~ Beach Wave (Fourteen Names for Thrift)

Full fathom five thy father lies

Of his bones are coral made

Those are pearls that were his eyes

Nothing of him that doth fade

But doth suffer a sea-change

Into something rich and strange.

The Tempest by William Shakespeare 3

The Solway lives in a liminal state, burnishing the edges of the salt marsh twice a day, each day, pushing England & Scotland further apart. The inner Solway Firth is home to one of the highest tidal reaches in the United Kingdom. A neap spring tide will rise and fall as much as 8 metres. The estuary is every day-cleansed with a saline solution. The sky is sand-papered by wind-blown grains. Every compass point stretches into thin lines, the horizon crenellated with hills. It is edgeland, a debatable space where you feel unimportant, that you begin not to matter. It is a distant, intimate and self-contained universe.

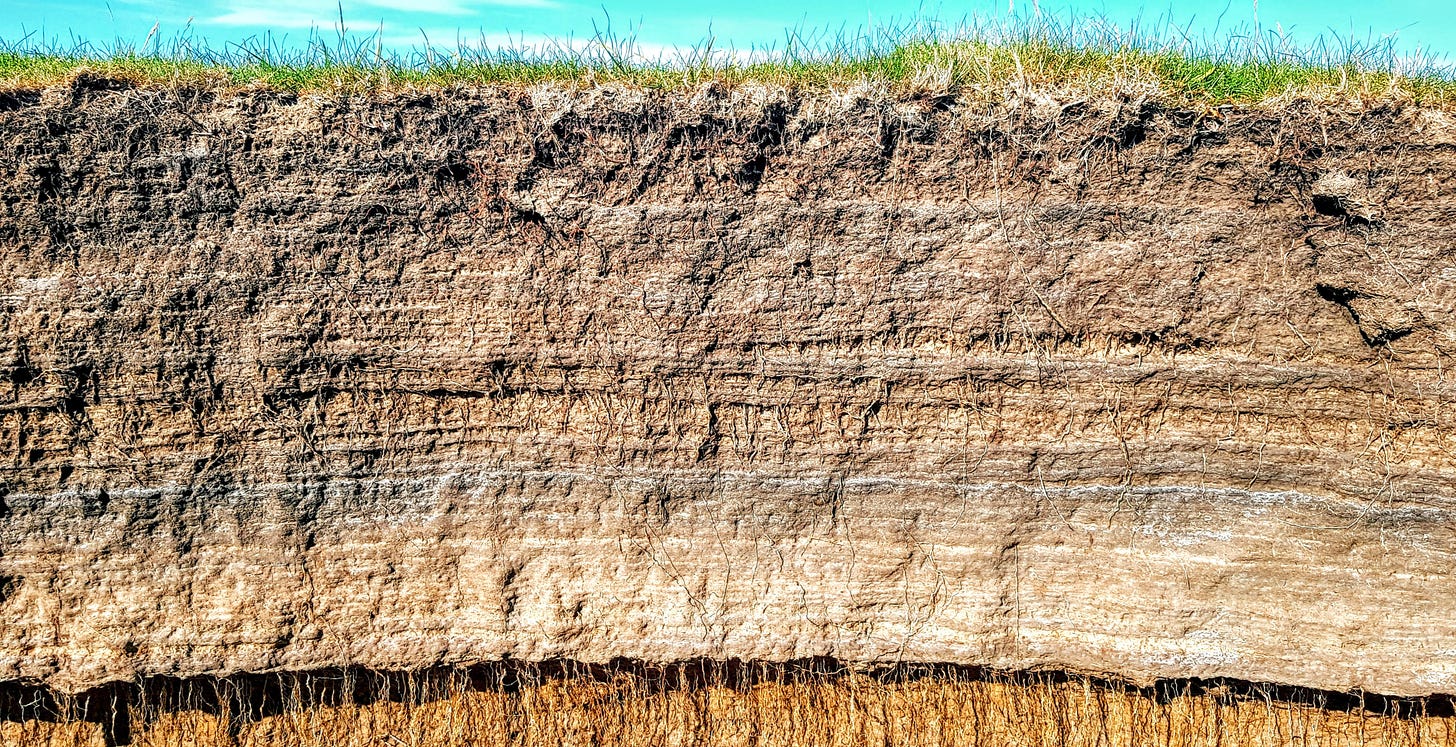

At the coastal edge, the sea nibbles away at the dunes. A northerly longshore drift stirs up the shallow silt. At the high Spring tides or when the wind is driving up the Firth, mucky waves deposit a layer of silt on the marsh. The grass becomes salty and unpalatable and is left to grow, a catchment area for the next deposit of silt. This is how the marsh grows upwards in laminations of sandy, salty, silt.

The Sand Cycle I – High tides pull the edges of the marsh into the estuary

The Sand Cycle II – High tides deposit the sand back onto the marsh

Here, on the level sand

Between the sea and land

What shall I build or write

Against the fall of night?

Smooth between sea and land by A. E. Housman 4

At the edge, step off the marsh grass, step through the erosion, onto the sand. It can be six feet down in places so you are hidden from view. In front and to the side, a mile of sand. No Blue Flag Beach can match this. The river lies still in the distance, ebbing out towards the Solway Firth. It is the safest time to visit the sandbanks, just after high tide, when you have a clear six hours before the water barrels up the funnelling estuary, its mini bore moving faster than walking pace.

Every year, the marsh grows in height and narrows in width. The estuary takes its offering from both sides and the land gap between England and Scotland widens. There is a yard less land to graze the salt-beef cattle on. The grazing of cattle and sheep on the Solway salt marshes is an ancient tradition. Annually, farmers gather at the local pub to bid on ‘stints’, each stint allowing summer salt marsh grazing for 1 beast or 2.5 sheep. Any cattle and sheep seen on the marsh that summer will be owned by many farms.

Here, at the world's end, is silence. All you can hear is the turning of the tide, the far-off cries from thousands of overwintering birds, and the unfaltering breeze that pushes the surface tension of the rippled sand over and over and over.

To the worlds end I thought I’d go

And o’er the brink just peep adown

To see the mighty depths below.

Birds Nesting by John Clare5

John Edward Masefield (1 June 1878 – 12 May 1967) was an English poet and writer, and Poet Laureate from 1930 until his death in 1967. Sea-Fever first appeared in Salt-Water Ballads – Masefield's first volume of poetry, published in 1902. He served in the Merchant Marine and his nautical poems Sea-Fever and Cargoes remain anthems of anthologies.

Sir John Betjeman, CBE (28 August 1906 – 19 May 1984) was an English poet, writer, and broadcaster. He was Poet Laureate from 1972 until his death. Betjeman had a lifelong love of the British coastline and visited Anglesea after discovering Welsh ancestry. He was buried at St. Enodoc Church, Trebetherick in North Cornwall, overlooking the sand dunes.

William Shakespeare (23 April 1564 – 23 April 1616) was an English playwright, poet and actor. Full Fathom Five is the beginning of the second stanza of Ariel's song in Act I Scene ii of The Tempest. Across many of Shakespeare’s plays, the sea’s agency can be felt in shaping the plots and characters’ lives. Even in the ‘landlocked’ plays, images of wild and boundless seas provide a vocabulary for ideas of transformation and sublimity, a sea change.

Alfred Edward Housman (26 March 1859 – 30 April 1936) was an English classical scholar and poet. Published A Shropshire Lad in 1896. Unpublished until after his death, Smooth between sea and land echoes his belief in the longevity and effacement of the sea over the short-termism of human activity.

John Clare (13 July 1793 – 20 May 1864) was an English poet. The son of a farm labourer, he

became known for his celebrations of the English countryside and sorrows at its disruption. He is now seen as a major 19th-century poet. His biographer Jonathan Bate called Clare "the greatest labouring-class poet that England has ever produced. No one has ever written more powerfully of nature, of a rural childhood.”