The Landscape of Lorna Graves

Lorna Graves (1947–2006) was an artist who worked across a range of media including painting, printmaking and sculpture. Her artwork is deeply connected to the Cumbrian landscape of the Eden Valley.

I sleep in the valley by the river. I work with clay, sitting with my feet in the water. I wonder in the hills above the Eden Valley and rest in a sheepfold sheltered from the wind.

Discovering the art of Lorna Graves was like falling through a portal into a subterranean world. Gateways and passages were early themes of the Cumbrian artist as she carved her artistic direction. It was a journey she described as ‘an unveiling, and the veils were made of iron.’

The poet Clare Crossman (1954 -2021) launched her memoir of Lorna Graves, ‘Winter Flowers, The Life and Work of Lorna Graves 1947-2006’ at Carlisle Bookcase on 22 March 2018. There by chance, I was moved by the words of Lorna’s friends and the Raku-fired pottery and paintings Lorna crafted.

The Eden Valley in Cumbria was an inspiration for Lorna. From the Neolithic carvings of Long Meg to the high-horizon line of the North Pennines, this landscape inspired her art. The following notes1 are from my Brampton Walkers are Welcome Guided Walk from Daleraven Bridge via Lacy’s Caves, Little Salkeld, Long Meg and Addingham Church on 10th June 2018 exploring the landscape of Lorna Graves.

Daleraven Bridge NY 565395

In May 1981 Lorna Graves held her first exhibition at Theatre in the Forest in Grizedale. She was awarded a £500 support grant from Northern Arts. A small piece in The Westmorland Gazette began ‘Hunsonby Potter wins £500 Grant!’ For readers, it might have been trivial news but for Lorna Graves, it must have felt like a momentous occasion.

Lorna’s search for artistic direction had been difficult, she described it as 'an unveiling and the veils were made of iron'. Born in Kendal in 1947, Lorna lived most of her life in close communion with rural Cumbria. Her mother worked as a hired hand on a number of Cumbrian farms. Lorna’s childhood was nomadic, moving from farm to farm, but it also gave her a unique reference to the landscape and the animals around her.

The local farmers could tell that Lorna had a strange affinity with the landscape. “Thoo’s touched” they used to say:

When I was a child they’d say ‘Thoos touched, thoo is’. Although it was a taunt I didn’t mind, it was a recognition. It felt like the truth. They meant I was mad of course, but to me it said that I was unlike them …. being touched was like being chosen, being linked to other worlds with different ways of being and understanding. When we worked in the fields, the barns and byres I loved every stalk and stook and bale of straw, every cow & every calf, the trees, the sky, the earth itself. It was a golden time. This was the whole universe. I saw and liked eternity. I tasted paradise.‘

Kirk Bank overlooking St. Michael’s Well

In 1350 the River Eden changed course and washed away Addingham Village and its church. Burials continued at the site for some time until floods once again swept away the graves. In C 16, on higher ground, the new St. Michael’s Addingham arose.

In times of drought, stone artefacts were retrieved and carried up to the new St. Michael’s including, in 1812, the base of a C 8 stone cross similar to the Bewcastle and Ruthwell crosses.

Encouraged by an inspirational geography teacher at Brampton Grammar School, Lorna studied Earth Sciences at London University and art at Cambridge before returning to Cumbria College of Art and Design in 1981.

Her first breakthrough in artistic direction came from an Art College project to study the Ruthwell Cross in Dumfriesshire, Scotland. The west face of Ruthwell Cross2 depicts Christ over the Beasts, the beasts crossing their paws in recognition of Christ’s divinity. The Latin inscription reads ‘Beasts and dragons recognised in the desert the saviour of the world’. In their blindness and smooth outline, these ‘beasts’ took on a monumental quality:

‘I recently began to draw an animal that figured in my dreams many years ago. It stood passively while people removed a lump of clay from the cut in its side. The large passive prehistoric animal standing in the city square is representative of the old primitive instinctive links with the earth that are separated from the culture we have now. I have followed the animal. It is like the land, like a huge gateway with legs and body across the top. The stillness is important. It is standing there wise. It has wisdom. It has vulnerability.‘

And so Lorna’s iconic beast was born. Alert, nosing the air. Her Raku animal sculptures were simply titled ‘Beast‘ and conveyed a permanent and powerful stillness. These non-specific creatures were neither calf nor deer, sheep nor bear, but the essence of the animal. At future exhibitions, gallery staff would find members of the public quietly meditating on these enigmatic sculptures.

Lacy’s Caves

Lieutenant Colonel Samuel Lacy, bought Salkeld Hall in 1790. His workmen carved five chambers out of the sandstone cliffs in the 18th C. Possibly he was emulating the caves at Wetherall further up the River Eden but at the time it was fashionable to have romantic ruins or they may have been built as a wine store. Colonel Lacy used to entertain guests here, and the area was planted with gardens. He even employed a man to ‘live’ in the caves giving the impression of a hermit-like existence.

Lorna now used the landscape around her as inspiration for her sculptures and paintings. She wanted to be more intuitive and began walking the landscape as inspiration. She built stone circles in Hunsonby Beck and a number of stone shrines along the riverside. Her drawings became windows, doors, archways, and spaces. Her early works were shrines to be approached, and passed through, an initiation from light to dark.

These caves created an environment Lorna loved. The red rocks, surging rivers, and gushing streams. Amidst the Eden Valley landscape, she was finding her stride. A diary entry reads:

‘I sleep in the valley by the river. I work with clay, sitting with my feet in the water. I wonder in the hills above the Eden Valley and rest in a sheepfold sheltered from the wind. The only way to get here is to wade the stream and climb the anvil-shaped rock where water drips down through a layer of mosses and grasses into the pool. The water is clear and deep; I swim where the fish swim.‘

Lorna also began to write poetry. ‘Nunnery’ inspired by the landscape down-river from Lacy’s Caves:

Wild wind rain leaves

And deafening waterfalls

Swift stained with earth

They’re in the dark leaf mould

Black red rock

In midst of spray

That waves my hair

Bathes my skin

Moistens wings

And thirsty soul

The nuns walked here

In ecstasy I’m sure

Filled as I am filled

With life and wonder

Long before the wooden walks

And bridges fell

Rotten down the chasm

Swept away to Eden

The Watermill Café, Little Salkeld

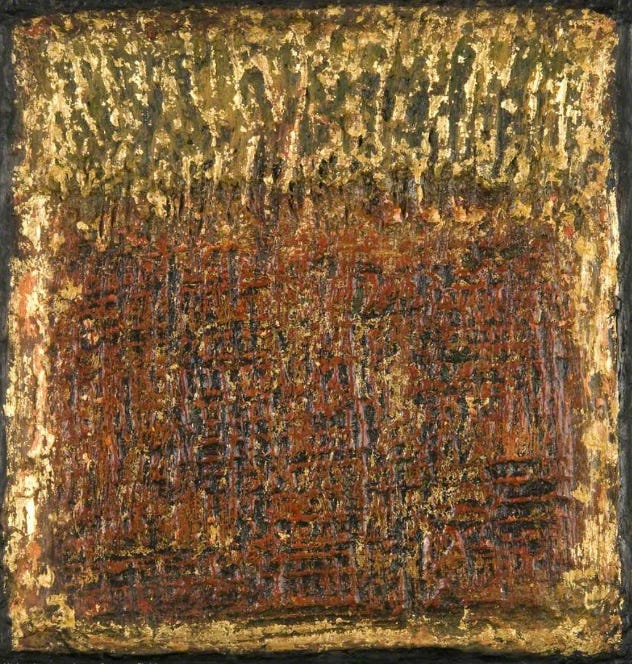

Lorna used the Japanese Raku "happiness in the accident" firing process for all her ceramics. Raku dates back to 1550 and was used for creating ceremonial tea ware for the Zen Buddhist masters. Raku touched on many of the things that Zen philosophy embodies i.e. simplicity and naturalness.

The Japanese Raku ceramic technique enabled Lorna to take her themes of transition and passage further, physically incorporating relics and artefacts within her work. The sculpted clay is biscuit (bisque) fired and set among leaves and wood shavings. As these catch fire and are consumed by flames the smoke and charred remnants become embedded within the piece. Her father’s ashes were given this treatment so that they became integral to the ceramic urn.

Lorna’s Second Major Theme - Wings, and the Winged Figure.

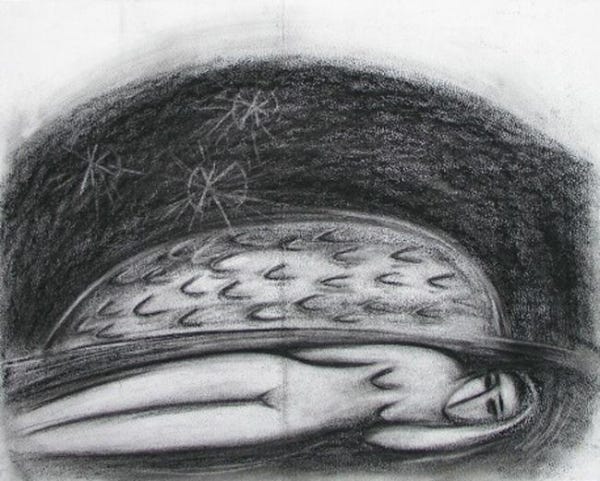

Winged figures had first emerged in Lorna’s drawings and paintings in 1982 and for some time she was puzzled as to how these insubstantial images could be translated into solid sculptural work. From stone-like sleeping geese to clay tablets with winged figures, culminating in her Long Series, begun in the late 1980s, of the female form sheltering under the curve of a tree-lined hill, a bird-pierced sky, a hogs-back tomb or a protective wing.

Lorna had followed her winged motif to such a spiritual conclusion that at later exhibitions, people would be found meditating close to her work. Here are two extracts from notebooks describing Lorna’s early encounter with ‘protective wings’ and how it links to consciousness:

My first memories of protective wings are from infancy when I lived in a wooden hut with my parents. The hut was raised above the ground. Underneath, in dust bowls I sat with the hens and gathered under their wings for warmth and protection. My consciousnesses was not separate from theirs. I sat in their nest boxes. Ducks and geese were my equal in height; their wings would brush against me … in the sound and feel of the sweeping feathers there lay strength.

At present, for me, the most important aspect of wings is a metaphor for consciousness in that it lifts us from our narrow earthbound existence. Properly used our wings (consciousness) enable us to be both protective and creative; to be the best of body and the best of spirit. By becoming aware of wings and winged creatures we become aware of and are linked with the air and sky. We have more space than we realise – the space above us.

One inspiration for the winged figure series can be attributed to the mystic artist Cecil Collins, a Tutor at the Central School of Art where Laura studied and a direct influence on her art. Collins was an idiosyncratic artist, his work full of personal symbolism. He believed that we are all pilgrims on a journey back to Paradise and that one of the functions of art was to help us on this journey. Collins’ images of angels as spiritual messengers of light and love flying over a mountainous landscape suggest the angel’s movement will cause the curtain to blow aside revealing a gateway to the treasures of childhood.

Long Meg and her Daughters

The antiquarian William Camden first wrote about the stone circle in 1586. Long Meg is the third-largest stone circle in England and the fifth-largest in the British Isles. It was constructed in the megalithic period between 3,300 to 900 BC, during the Late Neolithic and Early Bronze Age.

The circle consists of 68 surviving granite glacial erratic's, (26 standing plus Long Meg) arranged in an oval flattened to the north. The use of different coloured stones also seems to be significant – red, white and blue/grey predominate. There may be a red ‘equinox stone’ on the east side of the Long Meg circle (as at Swinside and Castlerigg), involved in the Autumn and Vernal equinox sunrises and sunsets.

Living in Hunsonby, just 1 mile from the stone circle, Long Meg was a constant source of inspiration, empowerment and fertile creativity throughout Lorna's life. In her notebooks, she writes powerfully about her physical connection to the ancient landscape:

I am lying face down in the grass with my arms outstretched and my palms and face against the cool earth. I can feel perfection seeping upwards out of the earth and into my body; into my limbs and chest and abdomen, into my cheeks and forehead. The beauty of the earth is absorbed into me like wine into blood. To stand and look is not enough; the sense then is all mind. The body must be pressed to the earth so that the mind and body are one.

I feel the past pushing up against me from below; the herds of animals, the vegetation, the people and their dwelling places, the winds and floods, the times of peace and the times of war, the chanting in temples and every moment of times past pushing up against me from the earth. The sound of the past like a thundering waterfall pours into me and I am absorbed; I am a libation. Slowly the past recedes and I am reformed on the surface of the earth.

Addingham St. Michael’s Church

In the churchyard stands the head of an ancient cross, recovered from the bed of the river about 1820. In 1913 various remains from the old churchyard of St. Michael were recovered from the River Eden; a hogback stone, a flat tombstone, on which is carved a cross and a sword.

Lorna always felt her painting and drawing were linked with the air and the spirit. The ceramics & sculptures with the body and the earth. She was on a journey to bring these two very different things closer together. Literary & philosophical on one side, the land and its people on the other. They complimented each other. Amid the impermanence of life, she saw a comforting continuity, often expressed by archetypal forms of animals, women, fish, boats, angels and standing stones.

If we cease to think of the land as environment and instead begin to think of ourselves as inseparable from all creation – breathing the same breath as the plants and animals – we will realise that the dust under our feet once breathed as we do; the moisture in the rivers once flowed in someone’s veins – there is no separation or boundary. There is no beginning and no end.

Looking east, sunset on snow Cross Fell

Where body & spirit pass over through one another

They form a cross; bringing together

Of opposites – to belong to both at once.

Here there is unity and where there is unity

There is freedom.

Lorna Graves won the Oppenheim-Downs Memorial Award in 2001. She exhibited in Britain, Japan, the US, and Germany. Her work was bought by many collections including the Victoria and Albert Museum. She looked at life as a journey – a passing through. Symbols of a voyage, flight, and the labyrinth, occurred frequently in her art. Amid the impermanence of life, she saw a comforting continuity. After her early death, from cancer, aged 58, her work, like her memorial set amidst woodland above Brampton in Cumbria, continues that voyage.

Download the 5.5-mile route at https://www.mapmywalk.com/routes/view/2419512460

The Ruthwell Cross is a stone Anglo-Saxon cross probably dating from the 8th century, when the village of Ruthwell, now in Scotland, was part of the Anglo-Saxon Kingdom of Northumbria. It is the most famous and elaborate Anglo-Saxon monumental sculpture standing and possibly contains the oldest surviving text, predating any manuscripts containing Old English poetry.